Text and images by Varduhi Kirakosian

Even locals swearing to know every single street in the city might struggle to spot addresses in Yerevan’s confusing and congested neighborhoods. But this doesn’t seem to be the case for Amy Todman, a Scottish born artist living in Yerevan for the past two years, who, I believe, finds her way around the city better than most.

This is my second visit to Amy’s apartment on Komitas Avenue, Arabkir district. I challenge myself to find her flat, refusing her offer to remind me of the way. Luckily, I recognize the familiar entrance where I notice wool, washed and hung to dry for sewing linen – a popular household tradition among Armenian women.

Amy is at the door. She greets me warmly just as locals are used to kissing on the cheek when they meet. As we walk into a quiet wide room filled with small and big canvases piled up in the corners, I ask Amy whether she gets along well with her neighbors. Amy describes the nice little garden she sometimes visits and notes, “I don’t know what people think, but I’m pretty quiet and usually, I stay by myself”. That quality gives her the chance to spend time on her own and feel free to create and experiment. Amy has been trying hard to learn Armenian since she moved here from Scotland. She finds Armenian very challenging and the language barrier is limiting and makes communicating with her neighbors practically impossible. “Until I learn well, and am confident to speak Armenian, really I can make friends with only those who speak English,” Amy explains.

“I’ve always made art,” Amy notes. She graduated with a Bachelors in Fine Arts from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design in 2003. Her first artworks were with textiles, which she exhibited through a number of installations. She was inspired by the process of making work that involved tactile materials like thread. In her early career she also worked in Arts education, working with a range of learners to explore what art might mean to them. For the next four years she lived in Leeds, England, and Glasgow, Scotland, where she worked on a range of public art and education projects. Amy kept the impulse to create and experiment with different media throughout the years, though she acknowledges that making art has always had a special impact on her, “driving [her] crazy in a way.” That’s when she convinced herself to “start being a grown up,” as she puts it.

Amy’s “grown up” years brought her to various art institutions as both an educator and researcher. At the Pier Arts Centre in Orkney she looked at the connections among landscape, museums and contemporary art collections. Her passion for nature deepened when exploring plant collections at the Glasgow Botanic Gardens, which formed the foundation for her Ph.D. in the idea of landscape in 16th and 17th century Britain. Amy spent several years working at the National Library of Scotland as both a curator and archivist, where she dove into their department of Manuscripts and Archives and worked with their Political Collections.

“But then I suddenly left everything. And here I am,” Amy laughs.

Right after welcoming me, she gets back to her work, sitting on the floor in the middle of her studio. I can see the full picture now: Amy seated cross-legged surrounded by her artworks, flanked by her recent sculptures and the one in progress. Amy presents me her works, excitedly showing me “The Brain.” “The Brain’’ is her recent sculpture, made of old newspapers, chicken wire, and flour and water paste (Papier-mâché). It’s quite big, maybe the size of forty human brains, and is symbolic of Amy’s journey. “The Brain” is the materialization of that side of Amy that is more analytical, methodical, organized and makes more logical conclusions.

“I moved to Armenia two years ago because I wanted to refocus, just make art. I wanted to feel more alive,” Amy continues thoughtfully. In 2018, with a developing creative practice, and a desire to engage with new cultures and communities, Amy wanted to work on her art, writing and archival practice in a new environment.

“I had reached a successful point in my professional career. I loved my job, but at some point, I felt unable to continue. Even though I always realized that making art has driven me to craziness, I realized at some point, that it is also the thing that makes me want to be alive. Once I understood that, the rest was easy.”

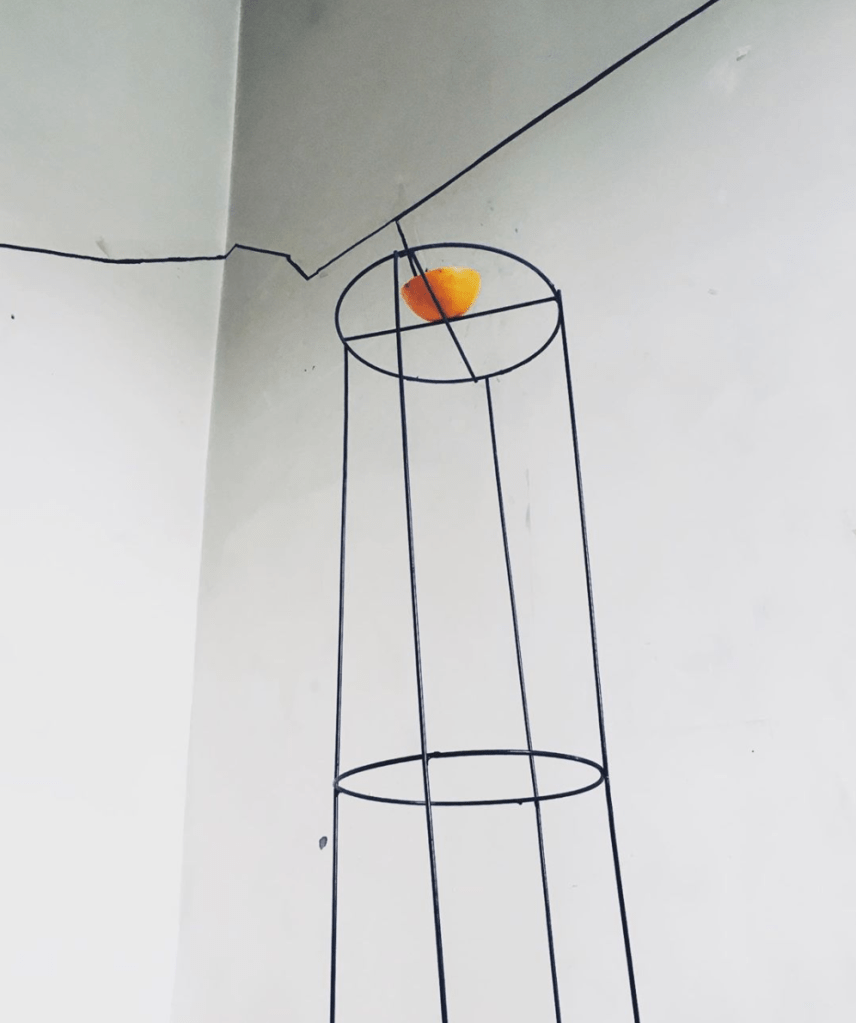

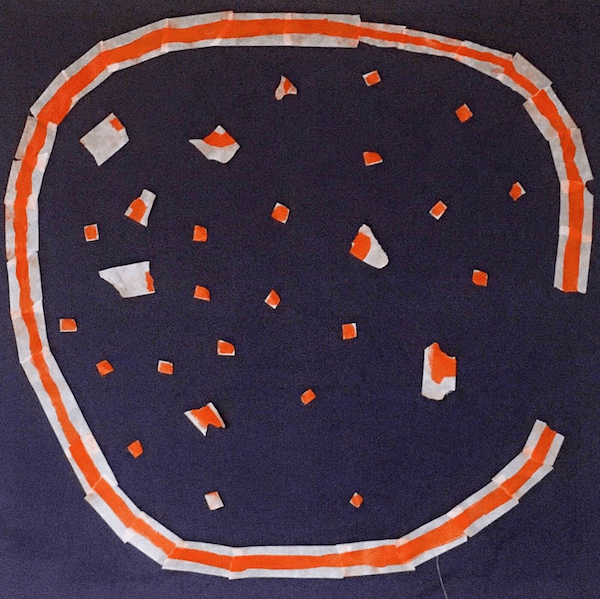

The idea of sculpting her own brain came from a need to separate herself from her brain. “I made ‘The Brain’ to be sure it’s out there, to be watchful of it and to remind myself to let go and be a bit more relaxed,” she reflects. In contrast to “The Brain”, looking at Amy’s artworks one notices repeating patterns, forms, shapes, and colors that resemble or remind us of oranges. Oranges appear in Amy’s embroideries and on canvases. For Amy, her oranges seem to symbolize a kind of chaotic energy in opposition to her analytical self. One could say the orange motif (life full of energy, vibrance and colors) represents Amy’s choice to leave everything and start a journey to the unknown. More recently this idea has developed into a sculptural intestinal form, physically wrapping the brain and perhaps symbolizing a kind of conflict or coming together. I don’t think she’s quite sure yet what it means.

Amy’s journey also appears in her work in the form of a long horizontal line that stretches from one side of the canvas to the other. I spot the identical line on the wall of her studio, as well as in a tattoo running the length of her arm. Amy has more journeying to do in Armenia. “I don’t have a plan to leave Armenia. My work flows here.” She also has some ideas for collaborating with the local artists. “There is something about Armenia that gives me room for exploring things and experimenting. It inspires me to make whatever kind of art I want without too much judgment, or criticism. I feel less pressure here in Armenia and I feel that Armenia drives me forward in my artistic journey.”

Amy has been profoundly influenced by images, colors, patterns, structures and systems of nature around her.

“Sometimes I feel at home in Armenia because there are similarities to the Scottish landscape. There is wonderful color in the Armenian landscape, shades of ochre, yellow, something flat, desert, but not desert, it’s something else. The color is very unique. When you come into Britain by plane and look from above, you see and understand the way that the landscape is arranged. The landscape is, among other things, an organized area. If we understand the idea of landscape as a kind of tension between chaos and order, natural and man-made, for example, then we see it reflected in our psyche, through the landscape and places we are surrounded by. The landscape feels less regulated in Armenia, and that is interesting for me, different to what I am used to. Armenia has its own way of being ordered and arranged, but it is not clear to me exactly what that is, whereas in Britain I understand the order more.”

Amy thinks there is more flexibility in the Armenian landscape. “I just walk around the city, look and feel. Because there are a lot of abandoned factories in Yerevan, when I walk, I have the same feeling as in Glasgow, which also has an industrial past. There, lots of old factories are repurposed as studios or similar places, and it is relatively easy for people to go in and do something: these areas seem to fit for doing some crazy stuff. I’m not entirely sure what I can or can’t do here, but I feel that these things are happening here too.”

Not only the nature, but even the basic distinct features of the neighborhood, be it the surrounding yard, a half destroyed building, or just the solar panels of a building outside her window, appear unconsciously or knowingly in the artists’ works whether through the colors that repeat or the forms and shapes. Amy’s work is meditative and ephemeral. She explains in her artist statement that ‘using drawing, found objects and words, my work explores the delicate territories of self and other, what’s around the edge, and what lies at the heart of the matter”. She “plays between imposed external control and trust in a process”. As curator, Anna Gargarian notes,

“[Amy’s] process is intuitive, yet disciplined. She is less concerned with the outcome (she calls her pieces “relics”) and more interested in what brings them to life. The tension we find in her work reflects a personal tension, as she oscillates between her identities as artist and archivist, intuitive maker and structure-loving analyst”.

Amy describes herself as someone very organized and detail oriented. She loves order and routine, which are at the core of her everyday life as an artist. “There are two sides of Amy,” she tells me; “Completely creative Amy, unpredictable, and there is very orderly Amy, and her very structured work. Amy can’t be both at the same time.”

Amy takes me to another room, small in comparison to her main work space. The walls are colored bright green and there is a large window that lets in enough light to make it another perfect studio space. “Some of my works I made here.” On the small work table, I can see Amy’s collection of map drawings. While I closely observe the works, trying to grasp the details, Amy describes the significance of the process of working and archiving within her artistic practice. Her progress partly relies on a practical and ritualistic approach.

It is interesting to see how Amy makes sense of her own journey as an archivist, art historian and artist. She reflects upon the influence that each of her professions have had on her art making. As a student of art collecting and the art market, she has learned to value artworks but at the same time look beyond what is art and what is not. “What defines art?” is a question that she explored during her studies. As an archivist, Amy believes she learned to take care of each thing she makes, however insignificant something might look, and put things in order, make sense of everything as she records her daily work. Art history, she thinks, helped her to develop an analytical and critical eye on her work. She observes her works in great detail and writes about them, creating a kind of conversation between her, the art work and the written description.

When asked about her future projects, Amy notes that things will change after her exhibition in Armenia. “The exhibition that we are planning for this fall is going to be an end point and a starting point at the same time. It will be the beginning of something new.” Amy has some projects in mind which she might be developing at the IN SITU project space. She is also interested in artist residencies in general. She believes that an artist residency offers a whole new environment where different artists combine and share a whole new energy flowing through them.

“I feel comfortable working here in my studio, I can’t say that I am attached to places, because I like moving a lot. It helps me to disturb the routine sometimes. For someone who likes following a routine, changes are needed to introduce novelty.” Though Amy likes change, she also longs for constancy and permanency, since being far away from home, the only way to develop a sense of home is to have a space where she can find herself belonging to.

***

From September 8 to 17, join us at Dalan Art Gallery for a solo exhibit of works by artist Amy Todman that take us on a journey “From here to there” across her daily artistic practice. Amy will be at the venue daily from 16:00 – 18:00.

Dalan Art Gallery

Open Daily from 11:00 – 23:00

Abovyan 12, Second Floor